rules to come, but first, our mission

One-hit wonders are fascinating. Think about it. There are some songs out there that are permanently imprinted on the popular imagination. You’re sitting on the toilet, and the song pops into your head. You’re at a basketball game, and the stadium plays a clip you recognize. You’re boozing with friends, and you all start singing. You shout “I love that song!” as you gleefully splash each other with bottles of Evian water. Now we’re partying.

When songs bring unbridled enthusiasm — and remind us that we all share an ape-like obsession with certain sonic vibrations — it is a rare and beautiful thing.

But even rarer is that one-hit wonders do this without relying on celebrity. You may not know who sang the song or when the song was recorded, but you still know the words and the melody. And so does everyone else. It takes a special song to reach all people in the same way, on merit alone.

My goal is to catalogue as many one-hit wonders as possible, and make a championship bracket of the 64 best. From there, the online masses can vote on a winner. After all, life is better with needless and arbitrary competitions. Ask my ultimate frisbee team.

who am I to do this kind of thing?

Am I really qualified? Well, I am the distinguished co-founder of a four-member music club, and I watched a lot of VH1 growing up. How’s that for bona fides? Plus, as a social scientist, I have a genuine, burning curiosity about what song will be deemed the best one-hit wonder of all time. Trust me, it burns hard.

Before getting to my process for making the bracket, a major challenge presents itself: how to define a one-hit wonder.

what makes a one-hit wonder?

One immediate problem in identifying one-hit wonders is that no band wants to be one. The term is often used as a pejorative. If you’re called a one-hit wonder, the implication is that you couldn’t provide the world more than one worthwhile musical offering.

For instance, ponder the “wonder” part. It’s shitty. I envision a hipster with a mustache tattoo rolling his eyes and saying: “You had one hit. What a wonder you are.” So much snark. Nevermind that this hipster doesn’t know how to write music himself, or do anything else other than woke-tweet about sustainable urban farming.

I learned “one-hit wonder” from my dad, Dicky D. And I continue to use the term because it’s recognizable. But I reject the judgmental tone. In fact, I would prefer “one-hit miracle.” That a band could make even one song that lives forever in our heads — without having the instant recognition of Madonna or Michael Jackson, and without commanding an industry-stoked legion of devoted fans — is impressive.

In fact, such a feat should be celebrated. Why? Because making a catchy, identity-free song that appeals to all of humanity is hard. That’s why there are relatively few one-hit wonders in the music pantheon. To join the cannon, the songs must kick an unbelievable amount of ass.

Hold on, now I’m talking about songs as one-hit wonders. But I’ve also described bands as one-hit wonders. Technically, isn’t the band the one-hit wonder, and the song the hit? Yes, and this brings me to:

the three characteristics of one-hit wonders

(1) the artist and the song are inseparable —

One does not exist without the other. In social science terms, they are “mutually constitutive.” If the Beatles didn’t have “Hey Jude,” they still would be the Beatles. But if the Buggles didn’t have “Video Killed the Radio Star,” they would not be the Buggles, as we know them. Therefore, in my book, the term one-hit wonder applies in equal measure to the band and the song.

(2) the song is universal —

One-hit wonders exist outside of time and context. Sure, they emerged in a context. They were once a part of a musical movement. On our list, there is dance, R&B, classic rock, disco, yacht rack, new wave, hip hop, 90s alternative, jock jams, and whatever the hell 12 Inches of Snow was. But over time, those classifications fade, and it doesn’t matter anymore. All that matters is that the songs are still known, and that they withstood the most difficult test of all — the test of time. On top of that, these songs transcend generational and identity divisions. They are familiar to dust-farting baby boomers and to porn-addled screen teens; to people in Harlem and to people in Hattiesburg, Mississippi; to people in all of Facebook’s gender classifications; and probably to people in Burkina Faso. They’re called Burkinabes, apparently.

(3) they are unpredictable —

In the moment they emerge from someone’s drunken bass riff and sublimate into the universal airwaves, future one-hit wonders are mostly unforeseeable. Did anyone really portend in 1985 that a Norwegian band called A-ha would make a song that millions of people would still listen to, and sing badly, in 2020? Probably not. By definition, one-hit wonders are not produced by seasoned performers with a tried and true formula. They are singular. Because of that, it’s hard to know in the moment that they will achieve ubiquity.

okay, that’s all pretty abstract, can you just explain what counts as a one hit wonder?

Man, you are pushy. But I get it. There is a lot at stake here.

If you look online, or search in music streaming platforms, there are a heap of one-hit wonder lists. I find them all pretty unsatisfying. Some lists include far too few songs, and they are unclear about their process. I think these are mostly from bloggers with names like Ambrose, who one night, while waiting for a Tinder date that would never come, quickly made an html list of his favorite songs. That’s fine, do what you gotta do, Ambrose. But next time, try to be more scientific.

Other lists include far too many songs, some of which can’t possibly count as one-hit wonders. For example, despite having a lot of success with “Whip It,” Devo is definitely not a one-hit wonder. They are known for a whole body of work.

To solve for the problems of both under- and over-counting, I made some rules.

rule 1. people today need to recognize the song — aka the Poco Rule —

It sounds pretty basic, but to be a one-hit wonder, a song must be immediately recognizable to almost everyone today. It’s not enough to have charted for a moment on Billboard back during Nam. The music must still be relevant now; it must get played on jukes, in cars, and on computers. It’s also not enough to have followers within a specific music genre. If the song is only known to country fans, punk fans, or rap fans, it is not a one-hit wonder.

Take, for example, Poco’s “Crazy Love.” This song charted at 17 on Billboard in 1979. It has a number of fans in a sub-genre of weirdo pop-country, and it is regularly included on one-hit wonder playlists. However, most people I talk to have never heard of this song, and cannot recognize the chorus. Ergo, it’s not a one-hit wonder. Subjective? Yes. But also very important.

rule 2. it can be a cover — aka the Rednex Rule —

On its face, the notion of a cover being a one-hit wonder seems antithetical to the whole exercise. So, you copy another song, and that’s your one thing? Seems unfair. However, there are some bands who performed a very well known older song, made it their own unique thing, and turned it into a big fat hit.

For example, in 1994 a group of Swedish freaks decided to appropriate Southern American culture by re-recording an already over-recorded old folk song called “Cotton Eyed Joe.” They added some over-the-top twang and a pulsing drum machine, and et voila, a one-hit wonder was born. No one was regularly listening to this song before Rednex, and now its all over the place. Like music herpes. Or glitter, if you prefer.

rule 3. the artist cannot already be famous before the song — aka the Belinda Carlisle Rule —

Part of being a one-hit wonder is not relying on celebrity, or any previous success, to make a new hit. The one-hit wonder arrives sui generis, like Venus from the frothy sea. This means that certain artists are disqualified if they have ever had a hit with another band before embarking on a new one-hit-wonder-like project.

For example, some people think that Belinda Carlisle’s “Heaven Is a Place On Earth” qualifies as a one-hit wonder. It certainly looks, sounds, and smells like one. It was her only huge hit. However, a few years before, Belinda C. fronted a band called The Go-Gos, who were a big damn deal. “We Got the Beat” and “Vacation” were both ground-breaking. If you doubt that, read Kathy Valentine’s new memoir. Anyhow, it’s fair to say that Belinda C. had experience, knew what worked, and used her knowledge to produce her mega-hit, “Heaven.” Not a one-hit wonder.

Caveat. You can be a one-hit wonder if you were in a band that had one big song, but then you left and joined another successful act. Basically, the one-hit wonder must happen before the other success. An example is Aimee Mann, who in the early 1980s fronted the group Til Tuesday, which performed the excellent “Voices Carry.” Aimee M. would later go onto an illustrious career as a folk singer-songwriter, and she would even do a cameo in The Big Lebowski. Regardless, Til Tuesday is still a one-hit wonder because it was before Aimee Mann was a celebrity.

rule 4. the band can’t have other super-popular songs –aka the Verve Rule —

Buckle up. This is the trickiest part of the whole son of a bitch.

Okay, here goes. A band can have a massive song that they are mostly known for, but to qualify as a quintessential one-hit wonder, they can only have one massive song. That’s by definition. Here’s the problem: how do we know that one big song is their only big song?

There is no way to know this for sure. After all, most bands produce many songs, and they put those songs on albums. It turns out, bands that have only one good, big song will still attract a non-zero number of fans that listen to their whole albums. And here’s the kicker, that small group of fans will get pissed when you call their coveted Ram Jam a one-hit wonder — even though it shouldn’t be an insult, as I explained.

I don’t want to point any fingers (at my friend Ned), so I’ll use myself as an example. When I was making the list, people kept insisting that Spacehog’s “In the Meantime” is a one-hit wonder. I resisted. “C’mon! Spacehog had so many other great songs! I mean, ‘Starside.’ And you can’t forget ‘Mungo City’ That’s a classic!” But here’s the deal. They did forget. And worse, they never knew. Spacehog’s entire catalogue is special to me (I see you, Royston Langdon), but to everyone else, they are synonymous with the song “In the Meantime.” I surrendered.

The challenge is that I had to make a measurable indicator that would help us resolve such disputes. My first option was to just check each artist’s Billboard chart history. However, that is deceptive. Thousands of songs once charted even though no one listens to them anymore. Sometimes a band has a song that, in 1983, out-charted the song everyone ends up remembering in 2020. Hence, Billboard Charts alone are not good enough.

To determine a one-hit wonder, I followed two steps. First, I checked their chart history. If they has only one hit on Billboard’s top 100–or usually much higher–then they are automatically a one hit wonder.

Second, if the band had two or more charted songs, I weighted the relative popularity of the song in question to their other songs.

The measure of popularity must include information on how much people listen to the song now. So I chose Spotify listens, and I made a rule that, to qualify as a one-hit wonder, the artist’s big song must have at least 8 times more listens than their second biggest song. This is called the Factor of 8 Rule, or the Verve Rule.

Why the Verve? Because on many lists, The Verve’s mind-blowing orchestra rock song “Bittersweet Symphony” counts as a one-hit wonder. However, for those of us who know a thing or two about the post-Britpop stylings of Richard Ashcroft, the Verve is much bigger than one song.

Wait, this sounds a lot like your Spacehog beef. Indeed. Entree the Factor of 8 Rule. According to Spotify, as of the time of this writing, The Verve’s “Bittersweet Symphony” has 445 million listens, a truly gargantuan number. This is upper-stratosphere one-hit wonder shit. However, their song “Lucky Man” has 68 million, which is also a crap-ton. 445 million is less than 8 x 68 million. Therefore, The Verve has more than one hit, and is disqualified from contention. QED.

Phew. I’m sweating. Okay, let’s finish these rules.

rule 5. the song needs must have been released between 1960 and 2000 —

This rule isn’t hard and fast, but I chose this 40-year period as the golden age of one-hit wonders. Why? For one, young people don’t know any songs before 1960, and old people really don’t know songs after 2000. Trust me. I think the reason is that this era was defined by what some critic nerds call “monoculture.” From the advent of TV to the beginning of the Internet, people saw the same shows, watched the same movies, and listened to the same music. Now, everything is fragmented. We order the stuff we like, and throw away everything else. Shut up, I’m not crying, you’re crying.

Point is, there are probably one-hit wonders before 1960. Everyone remembers “Little Girl of Mine” by The Cleftones! And there are undoubtedly some after 2000. Foster the People’s “Pumped Up Kicks” comes to mind. However, these songs are just not as universal as the others I will soon present to you.

how will you make the 64-song bracket?

I am following five steps.

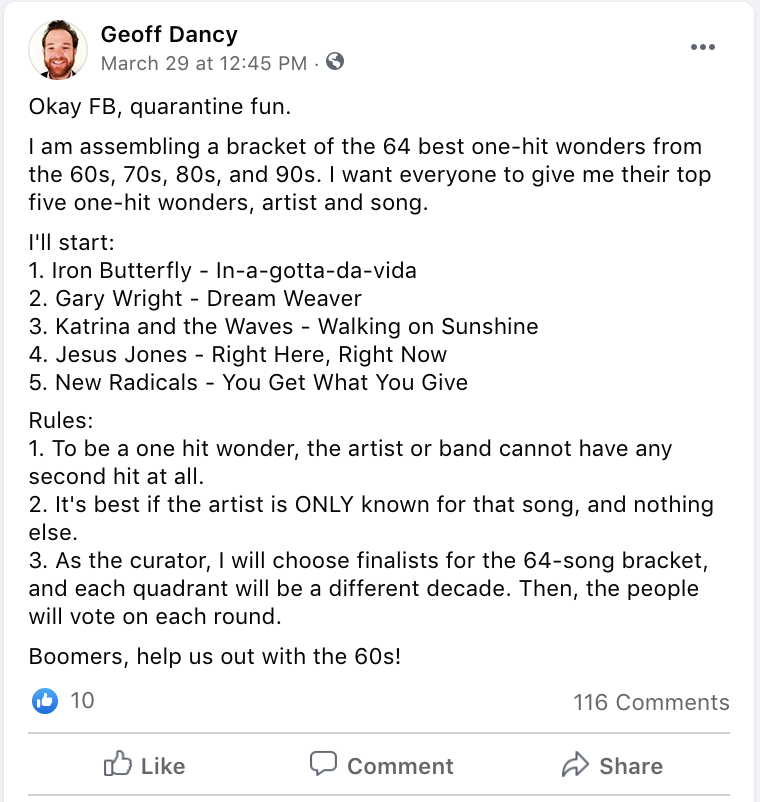

step 1. taking suggestions —

I started by asking everyone I knew on Facebook, and many of them by phone — which I’m pretty sure wore everyone out. But I got a lot of good leads this way.

step 2. compiling a list.

I put all of the suggestions ins a spreadsheet, and eliminated some based on my rules. I also scoured the worldwide interwebs for more songs I might be missing. Once finished I had listed close to 200 songs, 176 of which qualified as one-hit wonders.

step 3. team rankings.

I put together a team of 17 music dorks, including myself, from across genders and generations. Together, we split the full list into two groups of almost-90 songs. Group A covered 1960-1985, and Group B covered 1986-2000. Each team member then ranked both groups of songs from first to last. I took the average of all of those rankings. Out of this, I produced a list of the best 64 songs from each group. Click on this sentence to see an analysis of the full list and the rankings.

step 4. round of 128.

Again, the goal is to make a 64-song bracket of the best one-hit wonders for mass distribution. But to get there, we have to do a preliminary round of 128. This is a qualifying round for the final bracket. And this is where will be until May 15, 2020. Voting on the Round of 128 is now complete. As of May 7, we are in a Last Chance Qualifier round

step 5. bracket formation and web-based voting.

After the Last Chance Qualifier comes to a close, I will distribute the 64-song bracket to the masses. We will then conduct 6 rounds of voting, on the opening round, the round of 32, the sweet 16, the elite 8, the final four, and the championship. More to come!